In the real world there are inevitably multiple obstacles that light passes-through and bounces-off that disperse, colour and diffuse it in organic and natural ways. If you want to take your skills to the next level, always be thinking about how you can break it up – here’s 10 ways that i’ve come accross – we’ll start with a few basics and move onto some more esoteric methods towards the end.

One of the biggest creative challenges facing a cinematographer, once all the mechanical basics of correct exposure etc. are taken care of, is to ensure that a captured image doesn’t look “lit” (Unless thats what you’re going for eg. an actor on a stage performing a play) – This is one of the hallmarks of a beginner as light rarely travels directly from the source to the subject – it makes things look unnatural and subconsciously (or worse consciously) breaks the immersion of the audience. I have been guilty of this myself – in an attempt to ensure enough light i’ve made rookie mistakes like shining hard light straight onto actors from above… or sitting them in direct sunlight and then reflecting more of it back up at them to fill in the shadows created – I can’t imagine that was very pleasant for them… and the footage didn’t look great either.

It is worth mentioning here that most of these methods modify light in a way that will tend to disperse it in uneven and/or unpredictable ways, so it may need further control with careful use of scrims, nets, flags and curtains etc. Check out the related articles at the bottom of the page for more info on this.

1) Diffusion (Diff, Frost…shower curtain etc.)

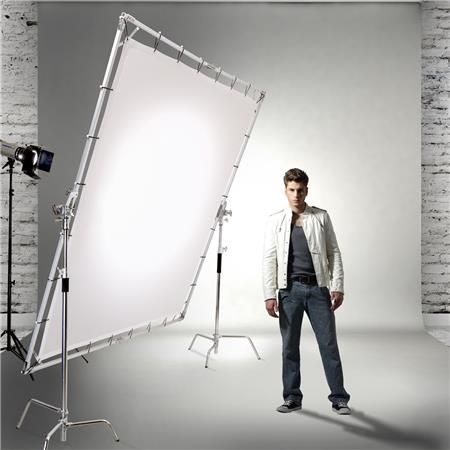

A common mistake is to think that diffusion alone is what makes a light source appear softer – It is in fact the size of the source that affects how it casts across a surface. We really use diffusion to vary the effective size of a source. Even a 12*12 silk will not produce very soft light if the lamp is placed directly behind the fabric – you need to fill the entire surface evenly (Plus it also means you won’t risk burning a hole in it!)

Professional polyester-based diffusion comes on a 4’ wide roll in a semi-infinite number of variations & densities from the main manufacturers (LEE, Rosco etc) – and though some of their names will change, (Eg. Hampshire vs Hammersmith Frost) you will most likely be using the following types most often – there is also a numbering system to make sure they can be used interchangeably.

“Full” – 216

“1/2” – 250

“1/4” – 251

The number is printed/embossed in very small text down the edge of the sheet so that you can still tell what it is after it has been cut from the roll. (If you find this is not the case, it only takes a couple of seconds to label a piece in the top corner with your trusty sharpie) There is a huge amount of information about these at the manufacturers website if you want to go full techie – however i have found that due to the enormous amount of crossover between different materials, its best to start with the basics and then try different things over time to find what you like best.

Though you can obviously continue to double up the thickness of diffusion to go softer and softer, a great material for making an already soft source (eg. KinoFlo) even subtler, is a closed-cell styrofoam called “Depron” (Aka. LiteBoard). It can be easily cut, and as a stiff piece has the added benefit that it doesn’t flap about in the wind making noise – always welcomed by the sound department. Plus it can double up as a soft-fill reflector if you don’t have any poly on hand either.

Then, for the even-more budget conscious among you, don’t underestimate the usefulness of common household items – some can even double up as set dressing. The classic DIY diffusion material is a shower curtain, which actually works very well. Others include tracing paper and bed sheets, however as none of these items are fire-proof, just be extra careful if using them with hot lights. I once shot some scenes set in a refugee camp where it was almost entirely lit with dimmed redheads tucked behind tea-stained sheets, hung from pieces of string – I was pretty pleased with the how it looked in the end.

Top Tip: If you’ve run out of trace frames but still need a 4*4 source (or larger)… Set up a C-stand with an arm facing out horizontally, then slide the roll of diffusion onto the arm and let the end hang down. To prevent the roll from spinning freely and coming undone in a big mess on the floor, fasten it to the arm using a couple of crocodile clips.

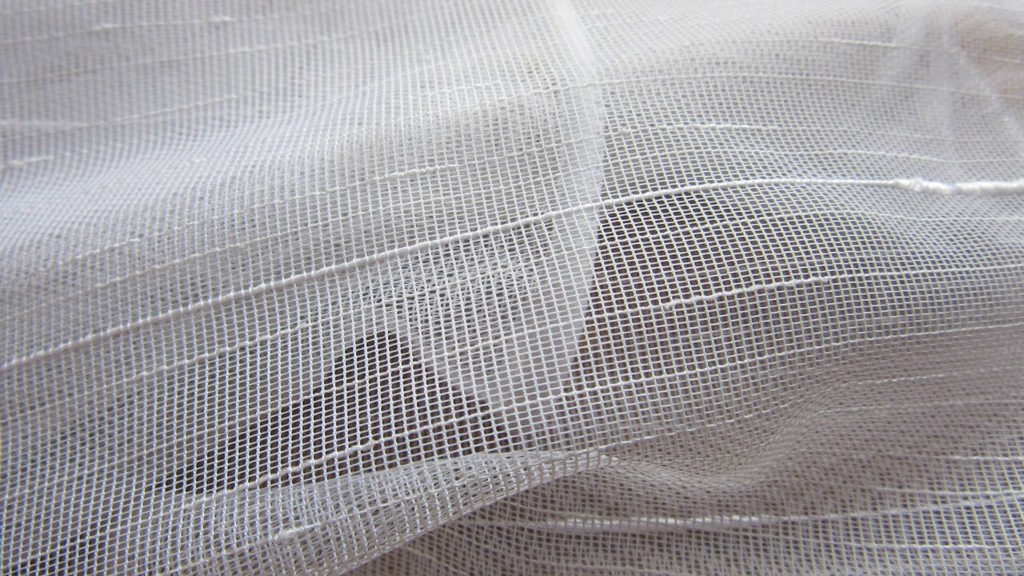

2) Gauze/muslin

Moving away from uniform polyester based materials takes us to loose-weave fabrics including Muslin, cheesecloth, gauze etc. Their effect is much subtler than diffusion ie. they will not prevent harsh shadows from a small bright source (In the same way that a scrim is a metal mesh that only reduces light output) – they are more suitable for creating further softness and irregularity from an already softer source. The weave pattern adds a randomness and organic quality that an even diffuser will not. Plus they offer complete freedom to be bunched/folded very easily to create light and shade in specific areas.

3) Curtains / Fabric

Let’s continue with the subtle/randomness theme and combine it with some more interesting shadows. Whether it be through printed or embroidered patterns – there are so many possibilities with curtain fabric to produce interesting results.

Placing a performer close to lacy curtain by a window will cast shadows of the pattern across their face – this is great for close-up work to create texture on their skin. It can evoke feelings of intimacy in our audience which counterpoint well with the fact that the character might be spying on someone through that window. ie. The voyeur themselves is also is being watched. (by us!)

On a more practical note, windows rarely have nothing in front of them (especially domestic ones) – and when shooting on location, we often don’t want to see what is happening outside. Whether it be that we don’t want the audience to be distracted by traffic whizzing past; or a particular garden filled with kid’s toys doesn’t fit the story of our lonely protagonist; or perhaps the story is set in a bleak mid-winter but you’ve had to shoot it in the middle of July; there are numerous reasons why hiding the outside world with curtains can be a useful storytelling tool.

4) Venetian blinds

Carrying on the window theme – the classic trope of Film Noir and 1940s detective stories is the harsh (preferably neon) light of the cruel outside world being filtered through the hard horizontal wooden slats of a venetian blind – simultaneously creating dark moodily lit interiors but also casting interesting light patterns across the walls and maybe our characters… you know, the latest smoking’ hot dame of a client with highly questionable motives; the smoke from her cigarette wafting gently up through the beams. Truly iconic and effective imagery.

Top Tip: If you don’t have a venetian blind, don’t worry – the audience won’t be able to tell that the blind is actually a series of strips of gaffer tape strung up between two carefully placed light stands.

5) Textured glass

Have you ever noticed how the glass in old buildings isn’t perfectly flat? Move your head side to side and objects in the distance will appear to wobble slightly. This is because the glass was made using various different processes that evolved over time and only reached the modern tolerances of flatness with the wide adoption of “float” glass in the later half of the 20th century. This can be used to great effect to add realism to historical sets – “The West Wing” did this in their recreation of the White House’s Oval Office. (Which is ironically itself is a sort of pastiche having been added to the late 18th Century White House in 1909, then later refitted in 1933 after a fire a few years earlier)

As the light passes through the irregular thicknesses it bends and warps creating a pleasing look to the image it casts. Take this a step (or two) further and you can more radically refract the light using textured glass. (typically used in bathrooms for privacy) Made by Pilkington by rolling molten sheets between metal rollers allows for a whole host of patterns to be available off the peg – from linear vertical reeds (think 1950s “Modern” architecture) to randomised cracked ice (unsurprisingly called “Arctic”)

Though these can be rented as prepared sheets and stored safely in flight cases in big trucks, smaller productions will suffer from being unable to transport such a fragile tool safely – However, there is quite a lot of plastic packaging around that can act as a stand-in DIY solution – a personal favourite of mine is Ferrero Rocher boxes that have a chunky diamond pattern moulded into a very clear polystyrene case. The trick is to place them just the right distance between the source and the subject to get the effect you need… and not melt them. Alternatively, many offices with traditional fluorescent fittings will still have clear polycarbonate diffusers with grid patterns moulded into them.

6) Foliage

What more natural way is there to suggest that the light coming in from an open window of the mountain-top log cabin retreat is genuine sun, than to break it up using a real branch? (Clamped or taped to a c-stand arm for making precision adjustments) It immediately suggests to the audience that there are trees just outside… of that hot and sweaty set tucked in a West London studio. Ahhh… you can almost smell the pine sap… No wait, that’s just the pound-shop air fresheners that the production team bought to hide the fact that the onsite loos drains are blocked again… Oh well.

Tangent warning: Not immediately obvious but every bit of foliage with tiny gaps between the leaves creates thousands of pinhole cameras that project an image of the sun – a simple circular dot onto anything below their humble branches. During an eclipse, one of the strangest side effects is that all these become tiny little crescent shapes, which is actually rather surreal if you ever get to experience it for yourself.

7) Cucoloris

Also known a cookie / cutter. This is a sheet of solid material – often metal (But also can be wood or plastic) with a cut-out pattern to resemble real world objects – like foliage etc. very useful where using the real thing would be impractical or is just unavailable. Eg. Shooting a jungle scene in an urban city studio.) Imagine filming over the course of days, weeks or months while trying to maintain continuity using real foliage placed close to all those hot lights – branches would break off, dry-out, wilt and die pretty fast… shedding leaves everywhere and potentially causing a fire hazard. Just a huge amount of work that can be saved. Not to mention the control that a more solid object provides.

8) Gobo (Static or Rotating version)

Though similar to a Cucoloris in their end result, the way they are used is quite different. Rather than being placed on a stand and moved around between the light and the subject, a gobo is a metal stencil, placed inside a spotlight (Like a source4 profile spot) that changes the outline and shape of the light beam. (Kind of like the reverse of how the infamous “Bat signal” casts a shadow onto a round spot)

As the inside of a profile spot gets super hot, these gobos are typically punched (or more likely laser cut these days) from a thin sheet of metal. There is basically no limit to the intricacies of shape that can be produced – just be aware that the proximity of the stencil to the source, means the shape produced will have very defined edges, i.e. hard shadows – So this might need some extra modification further along the light path to soften things up a bit.

9) Water (+ reflections)

Two options here:

1) “She sits beside the window thinking of where it all went wrong – The life she worked so hard for slipped through her fingers leaving her here, all alone. The worst part is how it could have all been so easily avoided had she just let go of the past. A small ray of sunlight begins to peak out from beneath the clouds and the warmth across her face reminds her that things will be ok… it’s just going to take some time”

Water running down a surface is a great way to break up light as it hits an actors face – Its a great visual metaphor for the emotion they are experiencing and can be achieved very easily. Rain is often available in the UK at least – but you can bet it won’t be there when you need it – no worries, this is the movies, we can fake everything! A garden hose, or even handy volunteer pouring from watering can, or jug (just out of frame) can sell this look very effectively.

Top tip: Glass can be cleaned with either a mild detergent or car shampoo to control the size of the droplets forming as the run down the surface. Keep a spray bottle on hand for top-ups.

2) The surface of water has long been a really tough nut to crack for computer generated imagery because of the sheer complexity of the how the surface moves and interacts to change the reflections and refractions (aka. caustics). We can use this to great advantage in the real world by using the surface of water as a reflector – most easily achieved outdoors where even a light breeze will cause ever-changing ripples. (Blade runner 2049 example) Swimming pools, lakes, reservoirs, even large puddles can be used this way.

10) Fire / Heat – Haze

“He staggers onwards through the sand, the heat is unbearable – water… water… its all he can think of. There in the distance, a shimmering pool of cool inviting life-giving liquid. He musters the last of his energy and rushes forward… but with every step he only gets closer the the crushing realisation… it’s just a mirage!”

This well-trodden (pun intended) cliche is just a manifestation of the fact that we are surrounded by gases – and these gases have physical properties that change based on pressure and temperature. Most notably is their “Index of refraction” (how much they bend light as it passes through) – Heat up the air and it will bend the light more. On those really hot sunny days we see how it makes objects in the distance seem to wobble.

We can use this to our advantage in film by shining our light through air (or liquid for that matter) that is being heated – turning it into a giant lens. The effect is quite subtle with small amounts of heat… but increase that heat – like with real fire – and it gets quite pronounced. Imagine the sheer scale implied by casting the light from “burning buildings in the distance” (a bright source shone through a smaller fire close by) onto a wall behind hero as they look on helpless to prevent the devastation.